Teaching Financial Literacy: An Age Guide

Finance…it’s not exactly riveting stuff. It’s not artsy or colourful or creative. In fact, if you’re too creative with your accounting you’re probably going to end up in jail. That said, having regular conversations about finances with your kids is on the ‘must do’ list.

Teaching financial literacy is far more difficult than it used to be. Finance has become largely invisible. We use online banking and credit/debit cards extensively. This has become even more the case as COVID-19 requires we limit the use of cash.

The consequence is that our children don’t ever see us earn money, put it in the bank, invest it or spend it. So, it is easy to see why kids think you can have whatever you want… just swipe a card! Australians also seem to have a blasé attitude to this invisible spending. We have the second highest household debt in the world.

What is financial literacy?

Financial literacy is the set of understandings and skills that allow a person to make informed decisions about budgeting, saving, donating and investing money.

Santa Maria College’s Business Studies teacher is James Rees. Before becoming a teacher, he worked as an accountant. He says that, “Most kids don’t know what financial literacy is and they are not provided with opportunities to learn first-hand. Reading about financial literacy is great, but if they don’t have first-hand experience of feeling good when they earn money and feeling regret when they over-spend, they won’t ever learn.”

As parents, we like to make sure our children are provided for. We want them to fit in and have the latest item of clothing or toy, but when we just buy them what they want, we stop them from learning. We need them to develop as responsible but not stingy in their approach to money. That doesn’t happen by chance.

What sort of financial experiences should we be giving our kids?

Tween Years (9 – 12ish)

Many children receive pocket money and that is a good place to start financial awareness, as the stakes are so low. At this age it is about life lessons; it isn’t about the money.

Instead of just giving your child money when they ask for it, give regular pocket money but make it reliant on them doing jobs. If they don’t do the jobs, they don’t get paid.

These jobs are extras, on top of their regular chores. Children still need to have chores that are part of their responsibilities in the family. They need to learn that being part of a community includes giving your time and effort. Communities work because we make these commitments.

James Rees says, “At this age, make sure your child understands the role money plays in their lives and how to complete basic transactions. This might be done through having your child plan the grocery shopping list with you online. Or give them a budget and go shopping together to purchase the items in person.”

We also need to model financial responsibility. Tell kids about some of the day-to-day financial decisions you make. For example, let them know when you can’t afford something and so choose a more accessible brand. Or when you consider an item or service is not value for money. Kids are highly manipulated by marketing, most assume that if something is expensive, it must be good.

Early Teens (13 – 14ish)

This is a time when teenagers can start earning some money outside of the home. Whether that be through a local paper delivery, sport umpiring or maybe working for the family business. There is also the potential for completing additional duties within the household that might not fall under the normal ‘chores’ umbrella.

Nobody expects an early teen to take on adult work responsibilities, but they do need to start somewhere. By the time they begin work in earnest you want them to understand what it is to have a boss and some of the responsibilities that go along with an income.

Rees advises, “When your young teen does earn money, help them to break their pay up into money they want to save and spend. You can discuss what they are thinking of buying with their new wages and whether that’s a worthwhile investment of their money. Don’t tell them…coach them. Ask questions like, “How long will it take to earn the money to buy the $100 shirt/ game you love?”

Mid Teens (15 to 18ish)

This is when your child will probably have their first job. The goal for all parents can be teaching them how to use a bank account, how to deposit money, how to get money out of the bank, and the importance of saving money. It’s helpful to do this online and in-person at the bank.

Rees explains, “It’s very easy when you get your first job to just spend all your money because spending money makes us feel good and it’s fun. This is a time where you can influence the spending habits of your child and teach them about saving for the future. You want them to enjoy their money but also learn to have savings in reserve.”

Too many people think being tight with money is being good with money. It’s not. We want our kids to be generous and charitable and also enjoy the benefits of their money. It costs money to live and money buys us opportunities. Being good with money means considering all of these factors and making well-considered decisions. Asking your child to pay their own phone bill is a way of making them understand that money gives us the things we value. It’s good to spend money on those things.

At 16 and 17, young people will be thinking about their first car. Rees says, “It’s understandable that you might want your child driving a car with a high safety rating. This may make you inclined to just buy them that car, but this is one of the great opportunities you have to teach your child about long-term saving goals. A good way of satisfying both needs is to come to an arrangement where for every $1 they save you will contribute an additional $1 to their car fund.”

Finally…

As our kids imagine their futures; the travel, living with friends, and having a good time, ensure they associate those opportunities with money that they will make. It is healthy for them to view making money as creating life possibilities. After all, that is the true value of money.

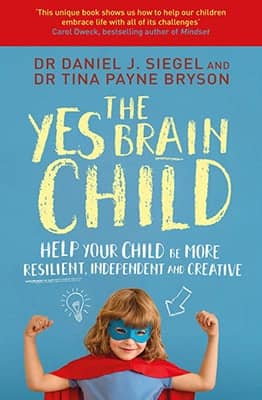

Remember, schools do teach general financial literacy concepts in specially crafted courses, like Santa Maria College’s Future10. There are also Australian Curriculum courses like Business Studies, which provides more detailed understandings. However, financial literacy requires ongoing, directed experiences. It also requires the emotional processes involved in real earning, spending, saving, and giving. That sort of teaching falls to parents.

Continuing the Journey: Carol Beins Upholds Her Daughter’s Legacy

This year, Carol Beins follows her daughter Shoshanna’s footsteps, journeying the same path as the former Religious Education teacher.

Exploring the Artistic Universe of Isabelle de Kleine (2011)

From childhood, Isabelle de Kleine’s talent flourished, guided by the supportive Art department into the renowned artist she is today.

What A Term! So Many Opportunities – Jennifer Oaten

As I look back on the past nine weeks, I am so grateful for who we are as a community and what we have achieved. Through the dedication of our staff and the enthusiasm of our students, we have established new connections, immersed ourselves in opportunities and worked through challenges.

- ConnectingLearning2Life, FinancialLiteracy

Author: Santa Maria College

Santa Maria College is a vibrant girls school with a growing local presence and reputation. Our Mission is to educate young Mercy women who act with courage and compassion to enrich our world. Santa Maria College is located in Attadale in Western Australia, 16 km from the Perth CBD. We offer a Catholic education for girls in Years 5 – 12 and have 1300 students, including 152 boarders.