We care about our kids, so why don’t they know it?

In the holidays I spent some time with Ms 8 who is a member of my extended family. She told me, “None of the grown-ups like me”. She has been in trouble at school and has been challenging her mum and dad at home. She is being defiant, arguing and acting out.

From the outside Ms 8’s behaviour is frustrating and difficult to tolerate. On the inside, she is doubting her sense of worth and place in the world. She is testing to see if she is loved or even liked. If this scenario sounds familiar it is because many kids go through it at some point, particularly in adolescence.

For their mental health and sense of wellbeing, every child needs at least one adult who is trustworthy, sees them, listens to them, and is deeply invested in them. It is the greatest protective factor we can offer a child or young person. As parents and teachers, we need to hear that. Hear it and truly wrap our heads around it. We. Are. The. Difference.

Most parents would say, “Well of course my child knows I’m here for them”. And they are. Yet, many kids are like my Ms 8 who is unsure, or simply not getting the message, that she is loved and valued.

Resilient Youth Australia report that in a sample of over 91,000 Australian children, 25% of Years 3 – 4 students say they cannot identify an adult in their lives who listens to them. This figure dips in Years 5 – 6 but goes up to 32% in Years 7 – 8 and 39% in Years 9 – 10.

These statistics are difficult to believe as an adult, especially as a parent or teacher. However, whether the numbers are correct or not is irrelevant, it is what a large percentage of our kids believe. Perception is everything. They simply don’t know that we are there for them. If we are, the message isn’t getting through.

The Disconnect

Where is the disconnect coming from? If we all love our kids and if we are all listening and here for them, why don’t they know it? There are a lot of good answers to that question.

1. Kids don’t read between the lines effectively

Our kids are quite literal. They do not infer meaning the way adults do; they are not skilled at reading between the lines. They also misread behaviours. As an English teacher I was often surprised when we read a class text and the students made a completely different meaning from the content to me, and from one another.

2. There is a natural negativity bias

Kids are hardwired to be negative. We all are. Back in our early evolution, there was so much detail and information in our environment that we evolved with a greater focus on the negatives…the threats. This attention to negative details is what psychologists call, the negativity bias. It has helped determine the success of our species, and it is especially strong in our young people as they are more reliant on the instinctive part of their brain, the amygdala.

Unfortunately, this negativity bias means your child or student will remember being told off for a lot longer than all the support you offer. It is a short walk from being told off to believing we don’t care.

3. Adults don’t communicate as well as we think we do

Often when we interact with adolescents, they seem a lot like adults. We assume they understand a lot more than they do. As a result, it is possible that we are not always communicating with our kids and students as well as we think we are.

This communication breakdown is most obvious when we discipline kids. When we say we don’t like a behaviour, they often hear it as, “I don’t like you.” This triggers a sense of shame and shame damages relationships.

Strategies for bridging the gap and building better relationships?

1. Use a 5:1 ratio

Education research reveals that we can achieve positive changes in student-teacher relationships by ensuring a ratio of five positive interactions to one criticism. This ratio has also been agreed on by relationship researchers. The positive interactions can be friendly conversations, specific praise or positive feedback, nonverbal acknowledgment, etcetera. Negative interactions may include criticism, reprimands, or simply not engaging as fully as expected.

2. Be clear

If we value a child, we need to tell them. Often, they will not recognise that connection on their own. Children need to hear:

- I love being your mum

- I love teaching you

- Talking to you before bed is my favourite part of the day

- I am here for you

- You can talk to me

3. Listen and reflect back

What we all want deep down is to be truly heard and understood. Your kids are no different. They want you to listen and then reflect back what you have understood, so they feel truly heard. Don’t fix the problem. Don’t compare it to a situation you’ve been in. Just stop talking and listen. If you don’t understand, ask for more information or ask questions. Don’t get bogged down in detail and facts, the most important thing to listen for is how the child feels.

4. Be careful with humour

Joking with kids at home, in a sports team, or in a classroom feels good. Humour builds a bond and creates a nice, relaxed atmosphere. Unfortunately, it can backfire terribly. Santa Maria College psychologist, Kimberlee Burrows says kids often share with her those unfortunate instances. “Kids will say, ‘My netball coach thinks I’m stupid.’ When I ask what makes them think that, they’ll explain that the coach makes jokes at their expense. Kids laugh along at the time, but the joke reinforces their low self-worth, and it stays with them.” Kimberlee explains that for many kids the coach, teacher, or parent is the all-knowing adult, so what they say matters, joking or not. This doesn’t mean we can’t use humour with kids, it means we need to avoid deprecating humour. Joke about things, not people.

5. Separate behaviour from the relationship

There are times when we can’t be positive and reaffirming with a child. They need to be corrected. This shouldn’t be a deal breaker. So, when a child says, “You just don’t love/like me,” the trick is to separate the behaviour from your relationship. For example, “Your choices and behaviours have consequences but that doesn’t mean I am ever going to stop loving/caring for you. The behaviour is bad, not you.”

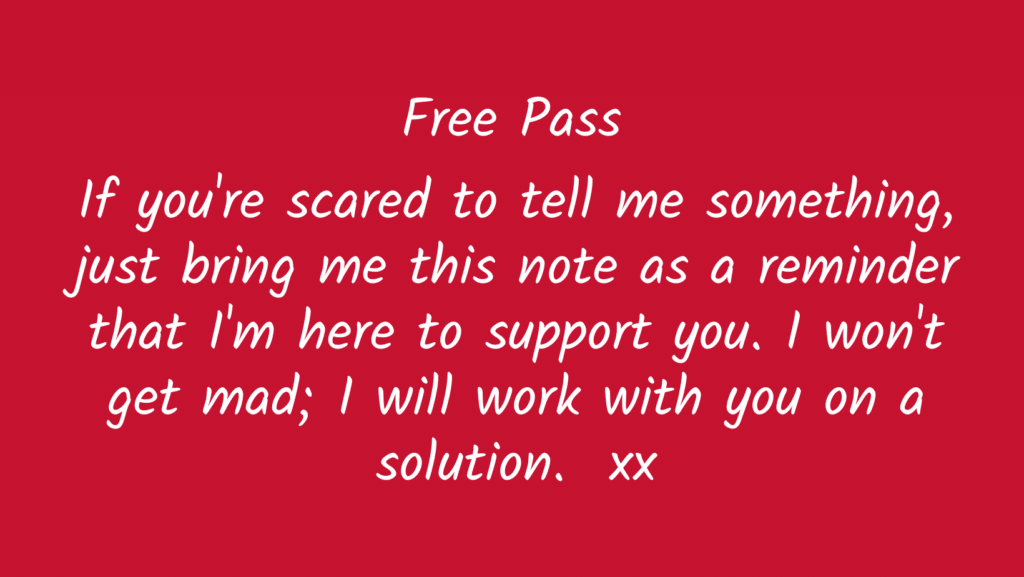

What if the child is telling you something you don’t want to hear?

This will happen because kids do silly things, we all do. A strategy that works well for some parents and teachers is a ‘free pass’. This is an agreement that an adult and child have that if something happens and the child is worried about the consequences of telling an adult, they have a free pass. It is a note that says, “If you bring me this note I will know that what you have to tell me is important and I will not get angry. I will help you.”

Final thought…

Little Ms 8 is loved, and she is fortunate to have many adults in her corner. Because she has communicated her feelings, changes will be made quickly. However, she is unusual in her ability to communicate so powerfully. Many kids will never articulate their sense of being alone. As adults, it is our job to ensure they don’t have to. It is up to us to meet them where they are.

Combating The Attention Span Crisis In Our Students – Jennifer Oaten

It is no secret that attention spans have been steadily declining, especially among younger generations growing up immersed in digital technology. The average person’s attention span when using a digital device has plummeted from around two and a half minutes back in 2004 to just 47 seconds on average today – a dramatic 66% decrease over the past two decades.

Weekly Wrap Up: Term 2, Week 2, 2024

Week 2 has come to an end! This Weekly Wrap Up features highlights from Scuba Diving Club, the Sisterhood Series, and Boarding ANZAC Service.

Santa Maria Teams Shine in Term 1 Sports

Santa Maria had a huge number of girls in the IGSSA AFL and Volleyball competition with strong results for a number of teams.

- Featured, Featured #MentalHealthStrategy

Author: Santa Maria College

Santa Maria College is a vibrant girls school with a growing local presence and reputation. Our Mission is to educate young Mercy women who act with courage and compassion to enrich our world. Santa Maria College is located in Attadale in Western Australia, 16 km from the Perth CBD. We offer a Catholic education for girls in Years 5 – 12 and have 1300 students, including 152 boarders.